A chance find while sorting through the effects of a well known and highly regarded Suffolk farmer has revealed a poignant story of love and loss from the Great War.

Lillian Mary Stubley passed away on the 31st October, 2020. Known as Mary, Lillian came from a farming family that settled in the Monks Eleigh area of Suffolk in the early 20th Century.

Found at the back of a dusty drawer, you might be forgiven for dismissing this small brooch as a piece of modern costume jewellery. However, this find has a story to tell, one without a happy ending, but one that also re-tells the story of the ‘Forgotten Battle’, involving some of the fiercest fighting during the closing months of the First World War.

The brooch was made by J. R. Gaunt of London, is of 15 carat gold and red/blue enamel. It represents the star of the Order of the Garter and has been associated with the Coldstream Guards Regiment since their formation in the 17th Century. The Star of the Garter was introduced by King Charles I and is a colourfully enamelled depiction of the heraldic shield of St George's Cross, encircled by the Garter, which is itself encircled by an eight-point silver badge. The motto, backed in blue enamel reads; HONI SOIT, QUI MAL Y PENSE, usually translated as ‘shame on anyone who thinks evil of it.’

The Garter Star badge is not unique to the Coldstream Guards but it is more associated with them than any other regiment. Its origin dates back to 27th May, 1660, when Charles II bestowed the Order of the Garter on General George Monck, the first Colonel of the regiment.

The Coldstream Guards are the oldest, continuously serving Regiment in the British army. During the 20th Century, it was common for members of the Armed Forces to buy their wives or sweethearts a gold or silver brooch of their Regiment, Corps or Branch; often while they were serving overseas.

Intriguingly, the brooch also bears a hand-engraved inscription: “Tom, 13 April 1918.”

And there the story might have ended - just a charming sweetheart brooch dating to the time of WW1. But who was Tom - and what happened on the 13th April, 1918? Did he get engaged/married on that date? Luckily, someone knew a little of the Stubley family history and suggested Tom might have been Thomas Dodridge, Mary’s cousin.

And so it proved to be. With the aid of the Family Bible and the wonders of the internet, a little research revealed Tom’s story.

Thomas William Dodridge was born in Hereford in January 1895, the youngest child, and only son, of Francis Ellery Dodridge (1861-1944) and Mary Eva Dodridge (nee Elliott, 1858 - 1952). Mary Dodridge was Mary’s Stubley’s Aunt (her Mother’s Sister).

At the time of the 1911 census, the family were living at 100 Wavendon Avenue, Chiswick. (The house apparently survived the Blitz and the first V2 attack during WW2). Francis’s occupation is given as a principal clerk with the Customs & Excise and was a sidesman (Assistant Churchwarden) for a number of years at St. Michael’s Church, Chiswick. He was elected People’s Warden in 1921, a post he held until he moved to the Suffolk countryside in 1925.

Thomas William Dodridge, then aged 16, is described as a treasury boy clerk.

Thomas enlisted with the Coldstream Guards at Chiswick Town Hall on 2nd March 1917, at the age of 22 years and 2 months. His enlistment form gives his occupation as a civil servant and states that he is 5 feet, 7½ inches tall. He was posted to Caterham on 3rd March 1917 (for Combat Training), and to the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards on 28th December, 1917.

His service record states that Private 21813 Dodridge died “on or since 13 April 1918” - the exact date inscribed on the brooch.

Thomas’s death occurred during the defence of Hazebrouck, which was one of the battles associated with the Battles of the Lys (7 – 29 April 1918), part of Germany’s 1918 Spring Offensive. For two days (12 and 13 April 1918), the 4th Guards Brigade (comprised of the 4th battalion of Grenadier Guards, the 3rd battalion of the Coldstream Guards and the 2nd battalion of Irish Guards) blocked the German advance towards Hazebrouck, while the British 5th and Australian 1st Divisions formed up behind them.

The story of this battle is an extraordinary one, described by Sir Frederick Ponsonby in the Household Brigade Magazine in 1920, as: “perhaps the engagement that will appeal most to future generations …the glorious stand made by the 4th Guards Brigade near Hazebrouck against overwhelming odds. In all the history of the different regiments, no finer performance has ever been recorded”.

The Guards Division moved to the Arras sector in December 1917 as the war on the Eastern Front ended and the Germans began to move divisions to France and Flanders. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had a manpower crisis in early 1918, with many line battalions, (but not the Guards), being disbanded to bring others up to strength.

In February 1918, 4th Guards Brigade was re-formed with 4th Grenadiers, 3rd Coldstream, and 2nd Irish Guards, and placed under command of 31st Division.

The German offensive began on 21st March, with huge gains along the line and over 20,000 British prisoners taken on that day. This was the Germans’ last chance of a swift victory before the Americans arrived, and they had made an impressive start.

The Allies faced the possibility of defeat with Sir Douglas Haig issuing his famous order on 11th April: “Every position must be held to the last man: there must be no retirement. With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause each one of us must fight on to the end.”

In his later despatch of 20 July 1918, (which described the fighting on the Lys), Haig wrote:

“The performance of all troops engaged in this most gallant stand, and especially that of the 4th Guards Brigade, on whose front of more than 4000 yards the heaviest attack fell, is worthy of the highest praise. No more brilliant exploit has taken place since the opening of the enemy’s offensive, though gallant actions have been without number.”

The reality on the battlefield was that the fighting was so fierce, that the Brigade suffered 80% casualties. Out of ammunition, tired and hungry, some of the skirmishes involved hand-to-hand fighting with fixed bayonets - in the dark. We might only imagine the horror at 23 years old.

The entry from the war diary of 3rd Coldstream Guards for 13 April 1918 reads as follows:

“During night re-adjustment of line ordered but not completed by dawn owing to difficulties in communication. Heavy fog at daybreak. Enemy armoured car gave trouble by driving up to K.10.d[.12.2?] and using M G [machine gun] fire on our posts.

6.30am Enemy attack developed on Centre and Left Coys [companies] - successfully repulsed on Right but by aid of fog he penetrated between Left and Centre Coys and gained L'EPINETTE FM.

Left Coy fell back on 4 G G [Grenadier Guards] at K.5.d. Gap of [400'?] at this moment between Left Coy and DCLI [Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry] just S E of ARREWAGE which No 1 Coy (30 men all told) attempted to fill. Nos 2 & 3 Coys left with flanks exposed & enemy working round them.

These Coys held on until surrounded on 3 sides then attempted to fight their way back. Very few succeeded.

Meanwhile, Left Coy heavily attacked by enemy at LE CORNET PERDU. This attack however was heavily repulsed. 2.0 pm Brigade front reported to be broken 12th KOYLI [King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry] having been forced to retire & enemy having penetrated our line to the left of 4 G G the latter were then completely cut off. Our No 4 Coy being in same trench as 4th G G were completely cut off. Bn HQ now moved to FM at CAUDESCURE and this line was then re-established to new parallel with and E of the FM BIEULIEU - ARREWAGE Rd.

At dusk, remnants of Battalion (about 40 men) collected and held [E&S] [?] of orchards at extreme SE of ARREWAGE. Quiet night, [rations?] & ammunition [supplies?] brought up.

Casualties for day: Missing Capt Whittaker, Lt Rowsell, Capt Elwes, 2nd Lt Carr, 2nd Lt Millar ; 2nd Lt Leadbitter; 2nd Lt Abrahams; 2nd Lt Ashby. O Ranks [other ranks] K in A 17, w [wounded] 84, M [missing] 259.”

Nobody knows what happened to Private Thomas Dodridge. Like so many men on both sides, his remains were never recovered from the battlefield. He is commemorated on the Ploegsteert Memorial in Belgium. His name was moved from the “On Service” list in the Chiswick Parish Magazine to the list of Missing in the July and August 1918 edition.

The address given for Tom’s parents on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) website is Water Hall, Kettlebaston, Ipswich. There is a record of Frances Hilda marrying John O.E.L Stubley (1868-1969) in Suffolk in 1927, and of their two children: Owen Colin F Stubley (1928 – 1982) and Lillian Mary Stubley (1929 - 2020).

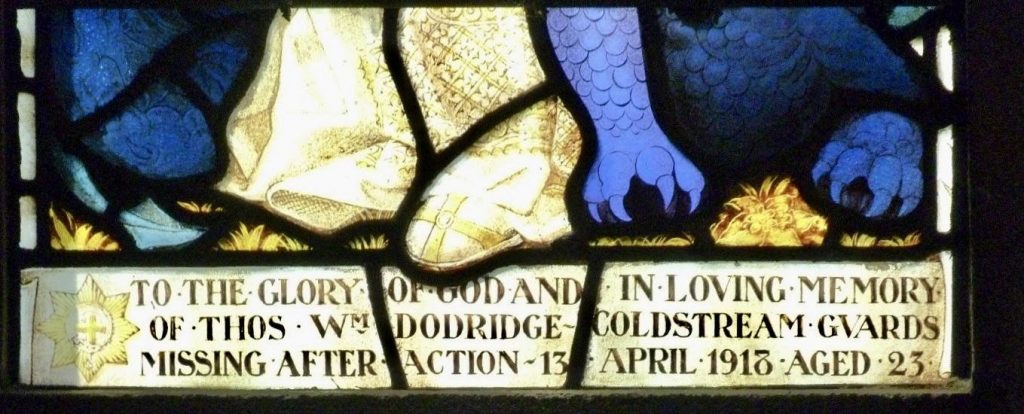

Tom is also remembered in a stained-glass memorial window at St. Michael’s Church, Chiswick. Like so many other thousands of young men, his death during the ‘Forgotten Battle’ doubtless broke his loved-ones hearts. His parents probably had the brooch engraved in his memory. And he - and his family are remembered today. Lest We Forget.

“If I should die, think only this of me,

That there’s some corner of a foreign field,

That is for ever England”

Rupert Brooke.

SOURCES:

St. Michaels Church, Elmwood Rd. Chiswick.

Wikipedia.

Borastan, J – Sir Douglas Haig’s Despatches, p227 (quoted in thesis – see below);

“The Battles of the Lys” – M.Phil thesis by Geoffrey Blades, King’s College, London (via www.nickpowley.com).

The Forgotten Battle - Hazebrouck 1918 - by Geoffrey Blades.

War diary of 3rd battalion Coldstream Guards (TNA, WO 395/1226).

Pte Dodridge’s service records courtesy of the Coldstream Guards archive.

Photos courtesy of Steve Newbold; Wikipedia; the Estate of the late Lillian Mary Stubley.

Blog By Jon Adkin